RESEARCH

Restarting the Dialogue among Honzōgaku Obsessives

Team Research on Honzōgaku begins. Nichibunken has been welcoming scholars from abroad to participate in team research that crosses the borders of humanities and sciences, academic disciplines, and the nations themselves. Dr. Itō Ken (pharmacist and Doctor of Pharmacology) of the Museum of Osaka University proposed an interdisciplinary study project on Honzōgaku titled “Reconstruing Honzōgaku as an East Asian Multidisciplinary Science: New Developments in Empirical Research on the Fusion of Arts and Sciences.” It had been decided that studies under this theme would start in the current academic year. I was surprised at first when Professor Liu Jianhui contacted me to ask if I would serve as a core member for a team research group focused on Honzōgaku. But, it must be said, I was also pleased.

In the Tokugawa-era, Honzōgaku was the height of a certain sort of intellectual obsession. People of that time drew on all manner of things from this world, pooled their intellects filled with curiosity that went beyond their social class, and researched and discussed the topic. In Kyoto too, Honzōgaku provided the foundations for science as it was conceived in Japan before the Meiji period. At places such as the Yamamoto Dokushoshitsu (Yamamoto Bōyō reading room), people ranging from Confucianists, physicians, artists, and poets to court nobles would gather together and enjoy participating in talks about honzō (plants, herbs, animals, and numerous rare products).

Our team research group is akin to those assembled during Honzōgaku's peak. For example, working together with medical researchers, we are performing chemical analyses of historical specimens of citrus fruits, which are thought of as the ancestors of medicine. We will work our way through our research results and also consider the history of citrus fruits throughout East Asia. This is truly the height of a fusion between the humanities and science, and of interdisciplinary analysis. Minerals as well as Chinese herbal medicine have been the subject of Honzōgaku studies. At Nichibunken, we have among our holdings the Sōda Archives, a collection of medical history texts. The members of the team research group are quite diverse. They include people involved in pharmaceutical manufacturing, plant researchers, and paleontologists.

We have absolutely no idea about what might result from these dialogues among “modern and contemporary Honzōgaku” obsessives that are about to begin here at Nichibunken. We are getting excited about what lies ahead. The excitement that comes from mixing up fields of scholarship and perhaps creating something from nothing in itself demonstrates the true value of Nichibunken. I very much want to lend a firm hand of help to Dr. Itō Ken in pursuing this research.

-700x526.png)

“Tokjiku no Kagu no Konomi”: Tachibana Oranges at Kitsumoto Shrine. Kitsumoto Shrine (Kainan City, Wakayama Prefecture) is dedicated to the legendary Tajimamori. The region is said to be where Tajimamori first planted the “Tokjiku no kagu no konomi” (thought to be the tachibana orange as known today) that he brought back from Tokoyo Province (or the Enchanted Land). There is a customary practice unique to this shrine of making offerings not only of sakaki evergreen branches, but also of tachibana oranges. A genetic investigation conducted by Team Researchers Shimizu Tokurou and Kitajima Akira ascertained that the tachibana orange has multiple strains. A local “citrus fruit movement” aimed at raising awareness about the region’s long involvement in cultivating the product, such as seeking registration for citrus cultivation as an important agricultural heritage, has arisen that draws on the historical studies of citrus fruits conducted by Team Researcher Maeyama Kazunori and myself.

(Photographs and text by ITŌ Ken, Osaka University/Visiting Associate Professor of Nichibunken.)

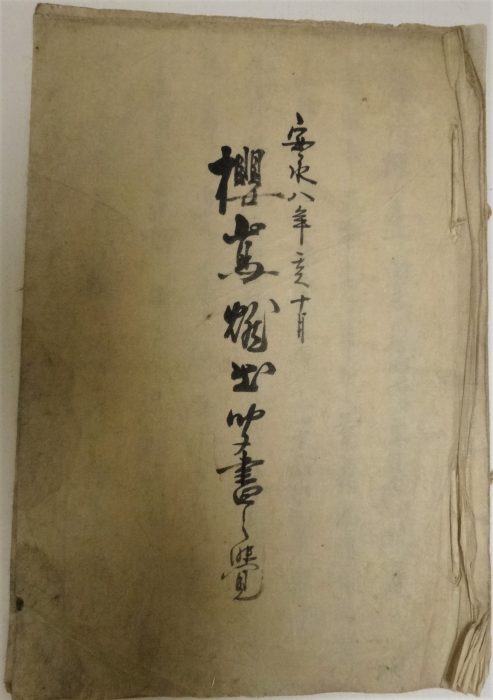

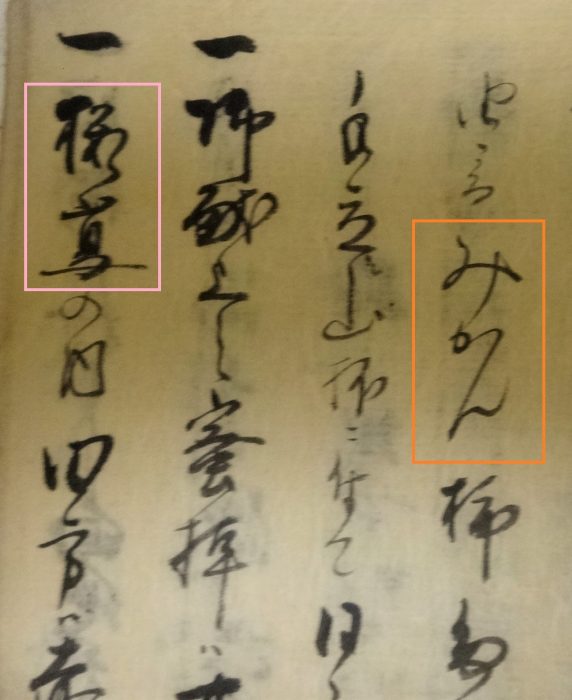

“Mikan” mandarin oranges were cultivated on Sakurajima in Satsuma Province, and they were also “gifted” to honored persons. There is a document that indicates that the plantings had been damaged by an eruption (Sakurajima yakedasare kikigaki no oboe, 10th month of An’ei 8 [1779], private collection). According to this document, the “gokenjō no mikan” (mikan to be presented as gifts) had been harvested before the eruption. Based on such records and actual Honzōgaku specimens, we conducted a team research on the true state of citrus fruits during the Tokugawa Period. (Photographs and text by ISODA Michifumi.)