RESEARCH

“Japan” as Portrayed in Western Music

From the early 19th century, many scores with Japanese themes for piano and voice were published in countries across Europe, in the form of popular sheet music. This trend predates the work of famous Japonists like Debussy’s symphonic poem The Sea, or Stravinski’s Three Japanese Lyric Poems. Prior to the spread of radio and records, sheet music was the most influential medium of musical distribution down to the early 1920s. What sort of “Japan” did this sheet music depict? From 2017 I began to investigate this issue, both here in Japan and overseas. At every step along the way, I became acquainted with a new “Japan,” and its charms.

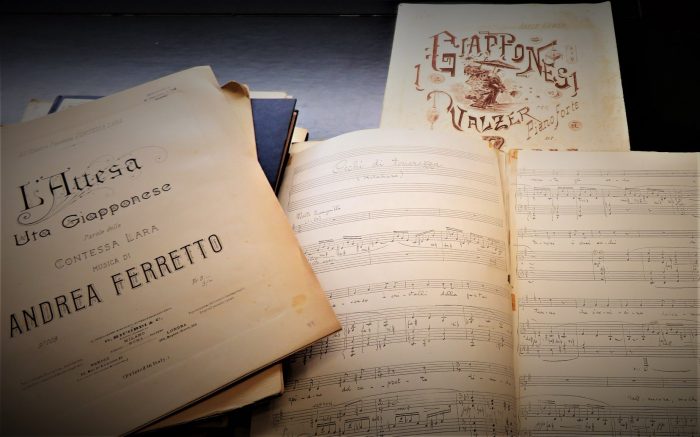

Music Encountered during my Italian Field Work (Photo: Mitsuhira Yūki, 2019.)

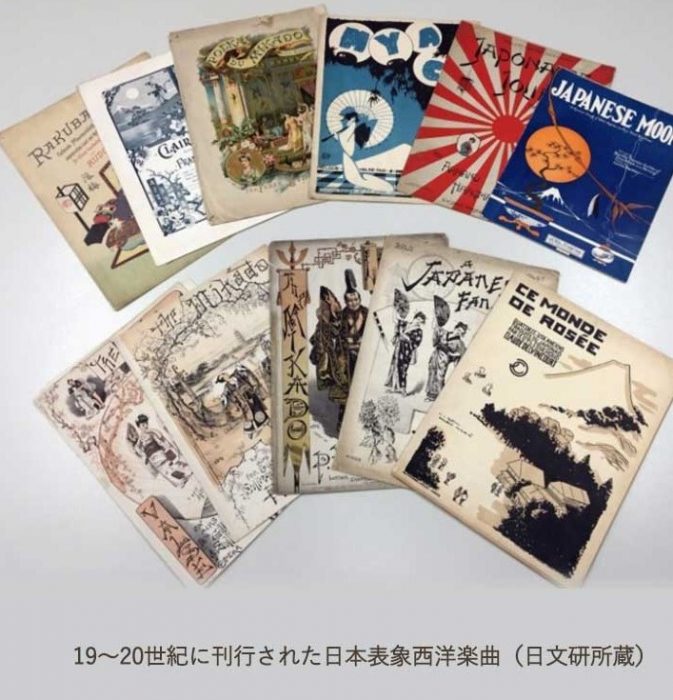

Sheet music featuring Japan in the title flourished among piano manuals from 1810 to 1840, like John Gildon’s A Japanese Air and Ferd Beyer’s Japanesisches Schifferlied. And then from 1850-1870 compositions emerged as a result of the cultural intercourse now taking place between Japan and Europe. A Japan boom on either side of the Atlantic saw the creation of operas such as Charles Lecocq’s Fleur de thé, and Kosiki. Operatic melodies were also arranged for simple piano accompaniment so they might be enjoyed at home or in salons, and these were published and circulated as sheet music or in music books. In the 1880s and 1890s, Japanese acrobats touring the West enlivened their performances with cheerful polka dances, while there appeared a flurry of music and paintings whose titles featured words of Japanese origin: mikado, tycoon, geisha, musume.

Western Music of the 19th-20th Centuries with Japanese Imagery (Nichibunken archive)

Into the 1900s, works prompted by the Russo-Japanese war start to appear, while the Western harmonies of Kimigayo and Education Ministry’s song Tenchōsetsu circulated widely. The production of the opera Madam Butterfly in 1904 found reflection in sheet music like Leo Edwards’ Mister Butterfly, and Joseph Samuels’ Chu-chu-san. From the 1910s onwards, songs based on translations of tanka and haiku, and instrumental music inspired by impressions from poetry and songs began to appear.

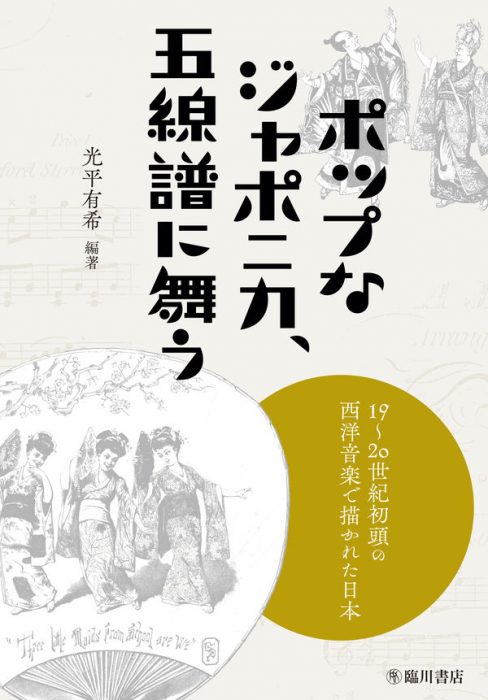

In March 2022, I published a book introducing the more than 200 pieces of music held in the Nichibunken library. (Poppu na Japonika, gosenfu ni mau: 19-20 seiki shotō no Seiyō ongaku de egakareta Nihon (Rinsen Shoten))In October, at an event styled “Ohanashi to ensō: mimi de kanjiru Japonizumu” (Talk and Performance: Japonism By Ear), I had the opportunity to experience these sounds for myself. My journey of discovery has just begun. My heart skips a beat as I think of the new “Japans” which I will encounter in the future.