COMMUNICATIONS

Summing up a Year at Nichibunken

The one-year fellowship has given me a vital opportunity to take stock of my research to date and to work on a book, Japanese Perceptions of Papua New Guinea: War, Travel and Reimagining of History (forthcoming from Bloomsbury Academic). Of the eight chapters planned, I completed the first drafts of four chapters. A chapter on veteran memoirs looks at how soldiers described the war—including accounts of how soldiers resisted or rationalized cannibalism to relieve their misery in the seemingly interminable hell. Another chapter discusses a war doctor who felt helpless in the face of rampant tropical disease and the dire shortage of medical supplies. The third chapter explores the making of documentaries. I examine the process of how the historical perceptions of the filmmaker and the people who appear in the film are imagined and created on the screen and behind the scenes, and the process taps into the emotions of empathy and shared pain in the audience. Readers may recall Yukiyukite shingun (1987) and Okuzaki Kenzō’s iconoclastic pursuit of historical truth. The chapter teases out how Okuzaki crafted his personality on screen and how director Hara Kazuo’s editing enhanced it. The fourth chapter is a cross-analysis of the cinematic adaptation of Katō Daisuke’s Minami no shima ni yuki ga furu (1961 and 1995). Each adaptation reflected the Zeitgeist of its times. While the 1961 adaptation celebrates Katō’s discovery of acting as his reason for living, the 1995 edition attempted to probe the tension between meaningful life and death. The other chapters draw on my previously published articles on Mizuki Shigeru (Japan Review, 2019) and writing about travels in various parts of Papua New Guinea.

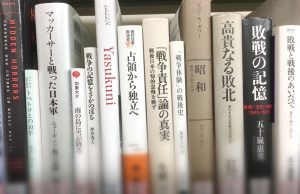

The New Guinea campaign of the Asia Pacific War is largely forgotten today. But the Nichibunken Library has many books related to the subject. The photograph shows books on the Asia-Pacific War, including those authored by Nichibunken faculty.

When I mention the topic of my research, the response is usually polite but disinterested. Such responses underline the general amnesia regarding the war among us today. My own response would have been the same had I not been fortunate enough to travel and encounter recurring traces of the war’s memory. I grew up in a family that never discussed history or politics. I learned about the Asia-Pacific War after I finished school and began studying, traveling and working outside Japan. Taking up my current position at the University of the South Pacific in 2012 exposed my glaring ignorance of the profound legacy of Japan’s imperial era in the Pacific Islands. The book is not merely an academic exercise but a personal attempt to fill the gaps in my knowledge that was not filled by stories from my grandparents or by my history teachers or textbooks. As someone once said to me, you do not necessarily choose scholarly work; it chooses you.

Dr Nishino at the 332nd Nichibunen Forum (November, 2019)

If I am to list one thing that I enjoyed most at Nichibunken, it was the academic freedom. Under the current climate affecting education, especially the humanities, academic freedom has become more of a privilege than a natural right. It took me some time to restore my self-respect sufficiently to benefit from academic freedom at its best. For this awareness alone, not a single day passes without feeling grateful to the faculty and administrative staff at Nichibunken—“Carpe diem.”

See also the expanded version of the introduction to Dr. Nishino’s research on the Nichibunken Facebook page.