RESEARCH

The Japanese Colonial Empire and the Global Linkage of Knowledge

“Viruses don’t respect boundaries” is one of the expressions that we have come to hear frequently during the Covid-19 crisis. From an historical perspective, it is clear that there has long existed an idea that pandemics need to be tackled beyond the framework of states. It was in 1907, long before the creation of the League of Nations, that a permanent international health organization was first founded in Europe. The International Office of Public Hygiene extended its reach into Asia and Japan after the First World War. There was a reality here that cannot be spoken of uniquely in terms of “international cooperation.” Historically, China had the restructuring of state and society imposed upon it in the name of international pandemic strategy. Again, the Japanese colonies of Taiwan and Korea were almost never recognized as members of international health organizations.

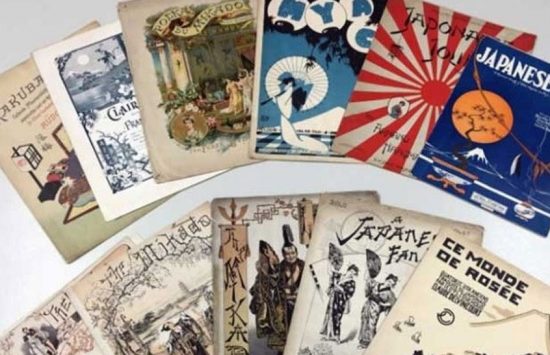

Behind this Team Research Group, which launched this year, were the aims of making sense of the global spread and linkage of such health-related knowledge, and of unpicking the hierarchical structuring of such relationships as those between “Western Europe and East Asia,” and “independent states and colonies.” The intention here is not to restrict the problem to networks of medical practitioners and hygiene bureaucrats. The global linkage of knowledge was after all diverse in terms of agents and contents. I refer for example to the educational activities of missionaries; to research into colonial cultures and languages by researchers of sovereign states based on Western knowledge; and to studies of Western colonial techniques of rule by colonial bureaucrats.

At the same time, it is my desire as group leader not to situate this Team Research as just another project in the now fashionable field of global history. Perhaps I could say that I wish to maintain contact with research into the colonial and imperial histories that pivots on the conflict and tensions between sovereign states and colonies. But I hope, too, to re-read those histories from within a broader context. I plan to spend the next three years exploring how to do research that locates colonial studies in the chain of global historical knowledge, without letting those studies be buried in global history.

Oxford College, which the missionary George Leslie Mackay established in 1882 in Tanshui. Mackay had been dispatched from Canada to the Japanese colony of Taiwan. This college became a pioneering facility for Western education in Taiwan, but tensions developed between Western missionaries, Taiwanese intellectuals and Japanese rulers. Today the college building is preserved as an archive on the campus of Aletheia University.