RESEARCH

Jidaigeki, as a Culture of Japan and a Culture of Kyoto: “Textures” created by a Field Research

Jidaigeki historical dramas are part of Kyoto’s culture industry; indeed, there was a time when the city was the movie capital of the country.

In 1897, industrialist Inabata Katsutarō showed movies for the first time in Japan in Kiyamachi, Kyoto. Then, in 1908, at Shin’nyodō temple in Kyoto’s Sakyō ward, Makino Shōzō—known as the father of Japanese film—shot the movie Honnōji kassen, in what is called the kyūgeki (lit., “old drama”) style that later developed into the jidaigeki. In due course some sixteen film studios were established in the city of Kyoto. After the Keifuku Kitano Line opened in 1926, five major Japanese movie companies—Nikkatsu, Tōhō, Shōchiku, Daiei, and Tōei—gathered, establishing studios in the city’s Uzumasa district, which went on to become the “Hollywood of Japan.” Unlike Tokyo, the scene of constant urban renewal, Kyoto had various advantages as a center of jidaigeki production, including its well-preserved traditional townscapes, myriad temples and shrines, and old traditions of kimono and other culture-related businesses.

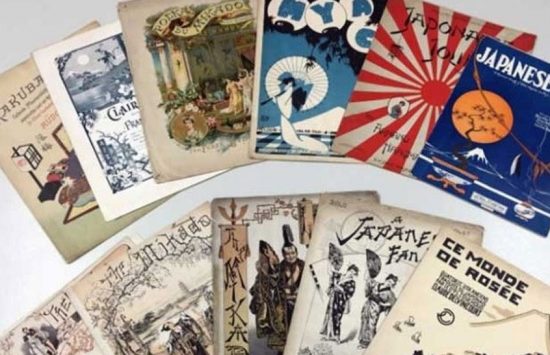

Examining costumes used in the jidaigeki film Hatamoto taikutsu otoko

I began to accumulate this kind of basic knowledge in conversations with Yamaguchi Norihiro, special advisor to Tōei Kyoto Studio Park. We agreed that the cultural and artistic value of jidaigeki needed to be re-examined using the historical resources existing in Kyoto’s film studios. This led to my project “New Field of Jidaigeki Research: Survey and Use of ‘Tangible and Intangible Cultural Resources’ at Tōei Studios Kyoto,” which was awarded a FY2020 grant-in-aid for scientific research. “Tangible” refers to costumes and “intangible” covers sword fighting. The project looks into jidaigeki costumes that have not been cataloged and compares the sword-fighting styles passed down at the Shinkokugeki drama troupe, Tōei Studios Kyoto, and Shōchiku Kyoto. In addition to closely investigating points of historical significance, the survey ultimately aims to create a digital archive of both the tangible and intangible resources.

Mr. Iwagami Tsutomu

Interview with Iwagami Tsutomu, chronicler of the Shinkokugeki drama troupe and specialist in manners and ceremonies (Interviewer : Yamaguchi Norihiro)

The archive is to be a global one featuring English translations and intended for spreading the culture of Japanese jidaigeki internationally, so as to contribute in turn to new film, television, and online productions. And, moreover, publicizing the archive as “textures” underlying an array of content not limited to the motion picture framework—such as gaming, anime, kimono industries and even their anime-inspired musical derivatives—can promote the widespread use of “cultural legacy” that the project is to survey and collect.

Mr. Sugawara Toshio

Interview with Sugawara Toshio, Tōei Studios Kyoto sword-fight choreographer (Interviewer : Yamaguchi Norihiro)