RESEARCH

As seen from the Periphery and from Below: What I Have Learned from the Japanese Popular Culture Research Project

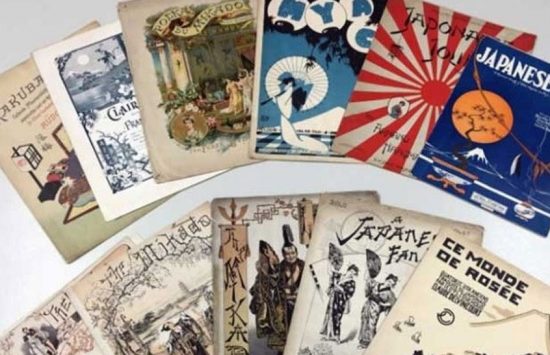

Nichibunken’s major research project on “Historical and International Research into Popular Culture to Pursue New Images of Japan,” which ran from 2016 to 2021, is now over. Among its outcomes are five volumes of the Nichibunken Popular Culture Research Series. These volumes are currently being translated into Korean and Chinese, and as this fact suggests, the project won plaudits not only here in Japan but overseas too.

Although the project has officially come to an end, through it I devoted six years of my life to popular culture, so my engagement is far from done. Indeed, my sense grows daily that it constitutes a new beginning. During the project, I came across countless “popular” cultural resources, which have enabled me to see things anew from the periphery and from below. Belatedly, I have begun to reconsider my own research framework.

I specialize in cultural relations between Japan and China, and so Japan’s China-consciousness and Japanese perception of China are important research themes. To get to the heart of these issues, I have until now focused my analysis on state policy, famous polemicists, and discourse within representative literary works. Thanks to the “popular” culture project, though, I came across the diaries of soldiers and travelers, propaganda pamphlets, and collections of photographs and postcards. Encountering them made me realize that within these sources there is a broader and more influential consciousness of, and imagination of, China. I now partly understand why it was that so many Japanese crossed to China during and after the Meiji period, acting out their fantasies about the continent. This was less about state policy and the discourse of famous people than it was the influence of a popular media, which had an overwhelming capacity to captivate and motivate these individuals.

There is a Chinese expression which can be read in Japanese as dattai kankotsu. It is different from the familiar kankotsu dattai, and is used to mean “being reborn.” This may be over-egging things, but there is no doubt in my mind that my work on popular culture has forced me to reflect on my approach to research. As I enter my sixth decade, I now look forward to a new set of challenges.