COMMUNICATIONS

The History of Modern Japanese Music

I joined the faculty of Nichibunken 16 years ago in April 2004. I consider myself extremely blessed to have entered such an ideal environment for research at the height of my career in my 50s. I remember I was surprised to receive a job suggestion. Having participated in a team research project there two years before, but knowing that the Center had no scholar specialized in music, I had thought they were not interested in my research. The offer came at a welcome time, moreover, just as I was seeking some change in my life, so I accepted without a moment’s hesitation. The research I was deeply involved in then was the history of modern Japanese music.

Professor Hosokawa presents at the 60th Public Lecture, September 2015.

Discussion with Professor Angelo Ishi, Musashi University (right), at the 14th Nichibunken-IHJ Forum, July 2018.

In 1989, when I was asked to write a series on the history of popular music starting with the Meiji era for a music magazine, I became aware that, although there were books about popular songs, shōka (songs for school music classes), military bands, film music, and other such specific topics, there was no survey history covering the whole subject. Music from Meiji onward received only meager space in introductions to Japanese music from ancient times to today or in dictionaries and encyclopedias. Realizing the importance of writing about the period from 1868 to at least the end of World War II, I eventually found myself something of a specialist on the subject. It seems that specialty appealed to Nichibunken and led to my appointment.

Explaining a slide at the 14th Nichibunken-IHJ Forum, July 2018.

(a slide presenting Carnaval Maru from the Carnabal in Bastos, Sao Paulo, in 1938.)

When I began the magazine series, I had just finished translating ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl's The Western Impact on World Music into Japanese, and I thought I would try to apply that perspective in writing about Japan. I learned from this book that the Western impact in the nineteenth century was not limited only to instruments, compositions, and orchestras; it also altered the venues and significance of performance, the musical notation, the educational systems, the audiences, and even the musicology. Moreover, the book revealed that the greatest impact was the abstract concept of “music” itself. It taught me about the clash of cultures between Western music and the instruments, language, sounds, and customs of indigenous music and the hybridization that influences from the West set in motion.

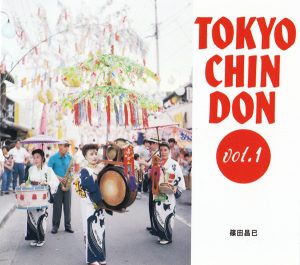

Tokyo Chin Don, vol. 1. CD (Puff Up, 1992.) Photograph by Kuwamoto Masashi.

Chindon’ya performer Takada Mitsuko around 1990. Photograph by Yoshioka Shigeru.

Around the time I began writing the series, too, I had been associating with the chindon’ya (street advertising) musicians, and that experience turned out to be important for me far beyond what I initially imagined. I decided I wanted to write a history that would show how even these self-taught musicians, who improvised on Japanese/Western melodies playing Japanese/Western instruments, overtly advertising shops while interacting with customers and wearing garish traditional costumes, were unwittingly steeped in the impact of the West. I wasn’t writing a history of Western music, of Japanese music, of musical compositions, of songs, recordings, or musicians. Rather, I was attempting to write a comprehensive history presenting various themes seen from diverse perspectives from street to concert hall. The chindon’ya seems to provide a crucial model for examining the hybridization of music cultures.

Ultimately, I could not complete my work before retirement (March 2020), but I believe I will be able to show something for it before long. I am grateful for the gift of the free environment at Nichibunken.

Members of Hasegawa Sendensha around 1990. Photograph by Yoshioka Shigeru.