COMMUNICATIONS

Applying Propp’s Morphology to Late Edo “Tales of Vengeance”

Vladimir Propp (1895-1970) is known for adapting the study of plant forms in biology to analyzing the “morphology” of works of literature. He believed that his own morphological types were analytically valid for all works of literature, and that he had succeeded in inventing a universal model. However, in actual fact, his research activity over several years focused on just one textual type, the dragon slayer narrative, corresponding to AT 300-749 on the Aarne-Thompson Tale Type Index.*1

Subsequently, in a variety of European countries there developed various structuralist schools, each of which proposed new types intended to overcome Propp’s methodological limitations. Each drew on Propp’s theory to develop their own distinctive models. Initially, scholars in different countries attempted morphological analyses of tales which drew on the thirty-one functions Propp had identified. However, it quickly became apparent that it was difficult to apply them to European tales and folkloric legends generally. This was because Propp used only Russian folktales, embedded in the traditions of the Russian people, for his own analysis. These tales all set out to depict people who had succeeded in Russian society as it was at the start of the 20th century. The values embodied in such literature were not common to other societies, or indeed to their literary expressions.

The applicability of Propp’s morphology requires that it be used for a society that shared with Russia a common human and social outlook. From this perspective, tales of vengeance (katakiuchi mono) from the late Edo period are perfectly suited to the application of Propp’s interpretations. This is because the corpus of tales of vengeance sets out to depict those who succeeded in the temporal and social circumstances in which the tales were composed. Almost all the protagonists in the tales are warriors, and warriors were the social group at the center of Japanese society at the time. Just as was the case with the protagonists of the Russian tales which Propp chose to analyze, so it was for Japanese warriors: to lose their status was tantamount to being cut off from social life, and revenge was the only possible way to reclaim that status. The protagonists in bakumatsu tales of vengeance are recipients of unjust treatment, and they achieve success only after suffering to “realize their desires.” The tales are stories of successful characters. Moreover, Russian folktales and Japanese tales of vengeance have a formulaic structure, with standardized roles for characters and a fixed set of elements—the basic units of action which comprise the plot of the story, which Propp calls “functions.”

To put all this another way, analyzing tales of vengeance in this fashion makes it clear how difficult it is to apply Propp’s morphology either to genres that do not share the same characteristics or to literary works of a different tradition.

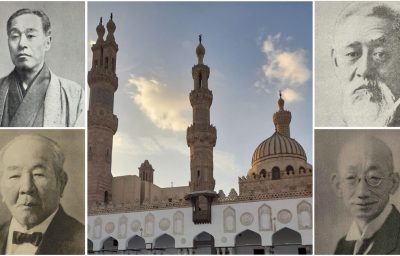

Vladimir IAkovlevich Propp

*1 Aarne Antti, The Types of the Folktale: A Classification and Bibliography. Helsinki: The Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, 1961.