COMMUNICATIONS

Rihō ōki: The Ōharano Progress and the Tennō no Mori Burial Mound

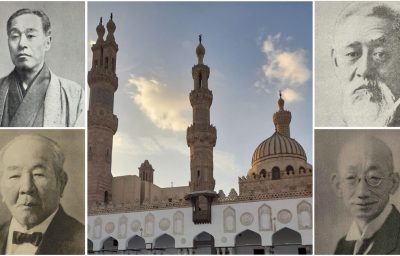

Take the 21 bus from Kyoto station to Nichibunken, and along Gojō Street you will pass the villa of a Genji court family and a site related to the Chiteiki. As you leave the boundaries of historical Heiankyō and cross the Katsura River, between the Goryōchō and Kokudō Sannomiya bus stops there is a small forest in the shape of a key-hole tumulus.

This is the Tennō no Mori (forested tomb of an emperor), 85 meters in length and constructed in the first half of the fifth century. It is the largest burial mound in the vicinity of Kyoto city. It appears that in the middle ages and the early modern period it was regarded as the tomb of Emperor Montoku, which is why the area was named Goryōchō (literally “imperial tomb site”).

Recently, I have been reading the Rihō ōki, the diary of Prince Shigeakira, son of Emperor Daigo. In it, I discovered an entry relating to this burial mound on the occasion of the emperor’s progress to Ōharano on the fifth day of the twelfth month of Enchō 6 (928).

Emperor Daigo proceeded from the Suzaku Gate to Gojō Street, where he turned west and arrived at the Katsura River. He left the Katsura road and entered the fields. When his palanquin reached the tumulus, he was served breakfast. The princes and courtiers sat on mats in the open. From the top of the tumulus, they surveyed the scene… The emperor then descended the tumulus’s path.

The tumulus would have been forested over, so if the party ascended to take in the view, a path must have been cleared. The mound is now thought to have been the tomb of the Hata family, but at the time was likely regarded as Emperor Montoku's burial mound.

If so, there may have been some symbolic significance in the fact that Daigo, of a different imperial lineage to Montoku, climbed to the top of the mound. The direct lineage of Saga, Ninmyō, Montoku, Seiwa, Yozei died out, which is why Kōkō, the son of Ninmyō, succeeded to the throne. Kōkō had his offspring all assume family names, and relinquish their right to succeed. However, Prince Minamoto no Sadami, Kōkō’s son, returned to the imperial family and came to the throne as Emperor Uda. It was his son Minamoto no Korezane who likewise returned to the imperial fold and succeeded as Emperor Daigo.

It is also perfectly possible, though, that Daigo regarded the grave of Montoku - of a different imperial lineage – as nothing more than a platform from which to view the scenery.

Emperors’ forested tombs are not under the control of the Imperial Household Agency, and so we too can climb them. Similarly, we may also ascend what in the 1860s became known as the Tamura burial mound, which is in fact the circular tomb of Uzumasa Mio, and dates back to the sixth century, the latter half of the so-called tumulus period. It is not far from Kyoto’s Narutaki station on the Keifuku train line. Of course, most Heian period emperors were cremated, and so there would have been no construction of tombs with large mounds.

Such are my thoughts as my days at Nichibunken draw to a close. I will no longer be able to set eyes on these burial mounds.

The emperor’s forested keyhole tumulus (Photo by the author)

The cover stone of a sarcophagus (Photo by the author)